From the way Allen Iverson dressed to how Metta Sandiford-Artest (formerly Ron Artest) acted during the infamous “Malice at the Palace,” it seems that the NBA somehow became a way for the American audience to perceive Black people and what it means to be or act Black. With a large portion of the population in the NBA identifying as Black/African-American, it makes sense that it has done this– incidentally serving as a platform for Black culture over the years.

When it came to the way Iverson dressed, it was too “hip-hop”, so Black people were “hip-hop”. When “Malice at the Palace” happened and multiple players were charged with assault, it reinforced the idea that all Black people are violent.

So suddenly, that’s what it means to be black?

No. It should be clear that all Black people are different and individual, just as any other person of any other race. But, for those who are not predisposed to Black culture on a daily basis or those who tend to stereotype, it isn’t that simple to understand.

So, the problem with the NBA as a platform for Black culture is not how it can be used to shape the perception of the great things Black players do, but it has become misconstrued as a place for people to generalize or negatively stereotype Black people, whether we realize it or not.

I: “Too Black”

The 2025 NBA Playoffs brought us physicality, intensity, and surreal plays. But, among everything, it brought us fashion.

Guards Shai Gilgeous-Alexander and Tyrese Haliburton made statements with their outfits off the court, often donning designer clothes and accessories through the hall–every piece coordinated to perfection.

While Haliburton told ESPN that Gilgeous-Alexander is “kind of the undisputed king of [NBA fashion],” for Gilgeous-Alexander, fashion is beyond the look; it is a way to express who he is. He told GQ that the most significant part of fashion to him is being able to express himself. “Being able to create something that’s your own and people can see a look and know that’s a ‘Shai Look.’ Being able to be an individual, that’s my favorite part…If I like it and I’m comfortable and confident in it, then I’m wearing it. It’s that simple.”

But what if Shai Gilgeous-Alexander wasn’t free to express his identity? What if the NBA wasn’t a platform for him or Haliburton, or any player to be individual– to be themselves? Would that be just?

Because, for years, that was the norm for the NBA.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the NBA institutionalized a culture that most resonated with the Black community; they embraced things such as hip-hop, music, and the streetwear style. They did this by creating an environment on the court that welcomed those things and also by showcasing them through the media.

Take a look at commercials, for example. The 1998 Sprite commercial (seen below), combining hip-hop, streetwear, specific slang, and gestures with NBA players, created a connection that added another layer to the NBA’s public perception as the “hip-hop league.”

But, by the early 2000s, this was suddenly seen as more “ghetto” than it was a way to bridge the community and embrace individuality.

The pinnacle moment that caused this shift? The Malice at the Palace.

On November 19, 2004, the Indiana Pacers played the Detroit Pistons at The Palace of Auburn Hills. After a scuffle between Pacers forward Ron Artest (now Metta Sandiford-Artest) and the Pistons’ Ben Wallace, Artest restored to lie on the scorer’s table to calm himself. With his hands tucked behind his head and his eyes closed, Artest was suddenly struck in the chest by a fan’s cup of soda. Invigorated, Artest rose with a start, jumped the table, and began attacking fans and anyone else who stood in his way, marking an infamous brawl in NBA history.

In the years after, those in and outside the league began to see it differently.

In 2007, three years after the brawl, sports writer Dave Zirin wrote, “The NBA higher-ups fear that ‘the public’ views pro ballers as one step removed from the yard at Riker’s Island. They are concerned that “Main Street USA” thinks the league is too gangsta, too hip-hop, too urban, all of which is code for “too young, Black, and scary.”

So what did the NBA do to combat this idea? They tried to clean up the league.

In 2005, the NBA introduced a new dress code: business casual only.

No T-shirts, shorts, or tank tops; no sunglasses indoors, no headphones in public; no headgear and no chains worn over a player’s clothes.

It may seem like players’ clothes were inconsequential to the reputation of the league in 2005, so why would this be a promising solution to the NBA’s problem?

Take a look at the way Lakers then head-coach Phil Jackson reacted to the new dress code. Per ESPN, he told the San Gabriel Valley Tribune, “The players have been dressing in prison garb the last five or six years. All the stuff that goes on it’s like gangster, thuggery stuff. It’s time. It’s been time to [introduce a dress code].”

That’s exactly it. The NBA thought that if they could get rid of the ‘do rag, bandannas, baggy clothes, and chains that people associated with Black people and violence, then they could get rid of the negative perception of the league.

While this may have been a good solution with the intent to raise television ratings, keep corporate sponsors and season ticket holders (i.e., make more money), it wasn’t the nicest idea for those who wore the clothes.

The dress code wasn’t even there to create a sense of unity like a uniform would, but instead fostered feelings of inequality and was there for the league’s monetary ulterior motive.

Former NBA player Allen Iverson–who rebelled against the dress code regardless of the hefty fines he had to pay–reflected upon the dress code, saying he felt like he was being targeted. “I was bothered by it, because I felt like they were targeting people that dressed like me.

When the NBA dress code was originally enacted, NBA player Jason Richardson also said he felt like it was being targeted to black players. “They want to sway away from the hip-hop generation. You think of hip-hop right now and think of things that happen like gangs having shootouts in front of radio stations,” he said.

He continued by expressing how he thought the dress code was racist, with players not even able to wear jewelry, like chains. “Just because you dress a certain way doesn’t mean you’re that way. Hey, a guy could come in with baggy jeans, a ‘do rag, and have a Ph.D,. and a person who comes in with a suit could be a three-time felon.”

II: “Not Black Enough”

In 2020, Kyle Kuzma, now a forward for the Milwaukee Bucks, wrote a letter on the Players’ Tribune titled “Ain’t No Sticking to Sports.”

In it, he states, “When I was a kid, some of the black kids in my neighborhood would say, “You’re not black.” But then, when I got to Bentley High, all of a sudden, I’m like one of the only black kids at an all-white school. I heard all kinds of racist things, racist jokes…I’m sure a lot of biracial kids have that kind of similar story of not being black enough for the black kids and not being white enough for the white kids. As a kid, you don’t know the history behind all that.”

Kuzma’s sentiment about not being “black enough” may not be seen with the same frequency and hurtful remarks in the NBA, but the sentiment is still simmering under the surface in the league.

In an episode of Golden State Warriors’ Draymond Green’s former podcast, Dray Day, Green discusses one of the reasons players in the league have negative opinions about his teammate Stephen Curry.

“He’s way more than what everyone expected him to be or ever gave him a shot to be. I think most people looked at it like, ‘Ah man, this a “privileged kid” growing up…People just automatically think that, ‘Man, this guy ain’t from the hood, he ain’t cut like that, he ain’t cut from a different cloth. He’s supposed to be soft and this, that,’” he said.

Adding, “Of course, Steph is light-skinned, so they want to make him out to be soft. So everybody just wanted to make him out to be this soft, jump-shooting guy and he continued to get better and better and better.”

So, on the other side of the NBA dress code, where acting and looking “too black” was seen as a negative thing, now players who don’t appear that way are seen in an inferior light by their peers.

But why is it that there are Black players in the NBA who can look at another Black man and think the only way he can be good is if he is from the hood? That he is not good enough unless he is every rough and awful thing the league has thought he was for years?

It’s because it’s something that is embedded in us, something bigger than the NBA.

Research has shown that one of the top three stereotypes associated with Black people (particularly inclined towards Black men) was athleticism, unintelligence, and loudness. This is a stereotype that has carried through sports for years. And the darker your skin, the worse the stereotype.

A 2020 study found that the commentators who covered several NCAA March Madness Tournament games described darker-skinned players by their physical characteristics, such as speed and strength, whereas they described lighter-skinned players based on performance and mental characteristics, such as being clever and “crafty.” This reinforces the stereotype and the idea that, at the expense of an innately athletic superiority, is a Black man’s intelligence.

(There has been no scientific evidence to support the claim that Black people are naturally more athletic than any other race).

Now, while these studies are not specific to the NBA, they both show the origin of the notions that players have about Steph Curry. We and those in the league have been socialized– primarily by the media– to believe that Black players are stronger and faster. And, the closer your skin is to white, the less of an athlete you are.

But just because you appear one way doesn’t necessarily mean you are that way.

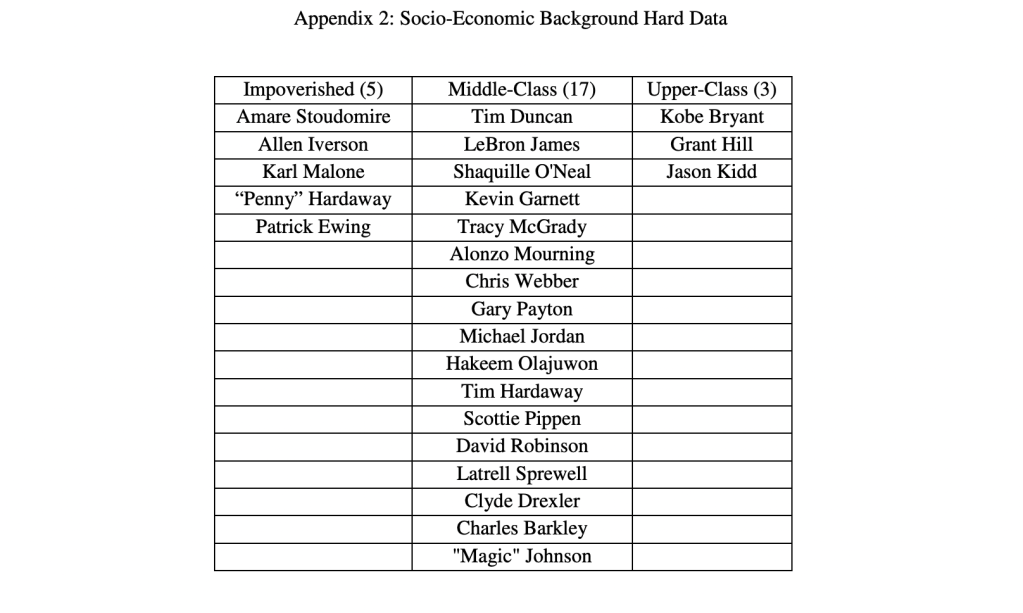

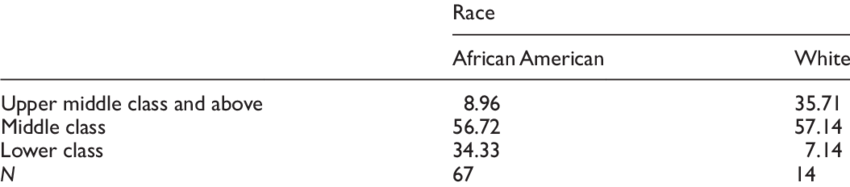

In regard to one’s environment (i.e., the hood), a study done at UCONN showed that the majority of All-NBA First-Team players from the late 80s to the early 2000s did not come from backgrounds of poverty; most were middle-class.

And in more recent years, another study found that among Black players in the league, most of them were from middle-class backgrounds.

So, therefore, you don’t have to be from the hood in order to be a player that succeeds and maintains a place in the NBA.

And in the case of Steph Curry, selected All-NBA first team four times, four-time NBA champion, two-time MVP, and eleven-time All-Star, being light-skinned and financially privileged doesn’t mean you’re not good enough to hoop.

III: Individuality

If the NBA is going to continue to be a place for people to reinforce stereotypes of people, players need to continue to be authentically individual. And we need to understand that they are individual.

Allen Iverson didn’t dress the way he did because he was a thug; he did it because it was the way the people around him dressed growing up. He got tattoos, not because he was a criminal, but because he liked the way they looked.

And Steph Curry grew the discipline and strength, not because he is from the hood, but because it was instilled in him by his parents.

The socioeconomic standings, race, and fashion of players do not exclusively define them as being a thug or not.

Because each of them and their stories are unique.

As Iverson took a look at the freedom NBA players have to dress now, he said, “Everybody can’t be the same. That’s why fans love certain people and different guys in sports. They have their own originality. If everybody was the same, you would like every player and everything. Wouldn’t no player stand out. It was bittersweet, and I’m happy I took the beating for it.”

To those who believed or still do believe that the players in the league are thugs because you saw the way they dressed or because you saw their skin, I pose the proverb they teach children in Kindergarten:

Don’t judge a book by its cover.

Leave a comment