Within urban neighborhoods across the world, people are facing a crisis. About 2.2 billion people in the world struggle with food insecurity; out of those 2.2 billion people, 1.7 billion of them live in urban areas.

Yet, there is an inadequate amount of initiative to attack this crisis.

Perhaps it is because it isn’t as simple as it seems. Food insecurity doesn’t mean people merely struggle to access food; it often means that people can’t get the right food—that of nutritional value—that fuels their bodies because, after a long day at work, they still can’t afford to have produce in their kitchen. Or maybe the problem has yet to be solved because it is even larger than that.

The root of the problem doesn’t lie in not having enough food; it is soiled in years of urbanization, poverty, and inequality that can find its way down generations’ mental and physical health. Food insecurity goes beyond the urban communities it affects in our backyard; it is a worldwide issue. An issue this big cannot be solved by one person or with one solution. We must come together to understand the causes and ramifications of food insecurity and then attack those issues at hand.

I: For the Families

In the wake of the devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity was at an all-time high.

Sharawn Vinson, a Brooklyn, New York resident and mother of six, knew she couldn’t keep her children under her roof if she wanted them to eat. “I woke up a lot of mornings crying. I didn’t want to get to that morning where I woke up, and I couldn’t feed them. So I didn’t have to worry about running out of food, I sent my kids to North Carolina to their dad’s house. I needed them to breathe; I needed to breathe. I was tired of worrying,” she said.

Sharawn wasn’t alone. From the years 2020-2022, about 875,000 New York families were food insecure due to the lack of access to food or the lack of wherewithal to buy food.

“There are so many people out here who are hungry–that have nobody. I have a half a couch, paint peeling off the wall, three beds for all of us,” Sharawn said, voice quivering. “But I got [my daughter], I got my grandson, I got my kids, and I got my life. What do I got to complain about?”

II: Who, How, and When

As urbanization has increased, so has food insecurity. According to the WFP Executive Board, “Over the last 15 to 20 years, the absolute number of urban poor and undernourished people has increased at an extremely rapid rate. Increased poverty, food insecurity, and malnutrition will continue to accompany this process of urbanization…for more than the last 20 years, development theory has reinforced the notion that food insecurity and poverty are generally rural problems.” If rural areas have a worse food insecurity rate than urban areas, it does not mean that urban families still aren’t facing food insecurity and its ramifications. This means that we are slowly realizing that the areas that we thought were blind to having bad food insecurities are actually suffering.

In one of the largest urban regions in the U.S., Los Angeles, 1 in 4 households are found to be food insecure. Most of these households face poverty. In 2024, a little over 40% of Los Angeles low-income households faced food insecurity.

Of those food insecure households, those identifying as Hispanic/Latino and Black/African-American were over twice as food insecure as those who were White.

With that said, simply knowing who and how many people it affects means nothing if we don’t take a walk into their homes. These families are scarred by food insecurity, both physically and mentally. Urban neighborhoods facing food insecurity tend to lack grocery stores that offer healthy food options, and/or it is easier to buy unhealthy food options due to lower prices and availability And suppose families try to go outside their area to grocery stores in non-food insecure regions. In that case, higher grocery prices in these neighborhoods may make local fast food appear more sustainable. Eating these unhealthy foods, filled with added sugars, trans-fats, and high sodium, can lead to chronic diseases, such as type two diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. In addition, those who cannot afford to have three meals per day are at risk of low blood sugar from skipping meals, which can also lead to diabetes complications and other health problems if the poor diet pattern continues.

Research has also found food insecurity doesn’t simply impact families physically; food insecurity within families is linked to poor mental health. Children who grow up in food-insecure households are more likely to experience mental health problems that lead into young adulthood. And it is particularly more prevalent for children whose caregiver(s) are also facing poor mental health and stress due to food insecurity.

In another study, young adults (ages 24-32) facing food insecurity were found to be more likely to battle with depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts along with sleep problems (difficulty falling and staying asleep). The study found that about double the number of participants who were food insecure were diagnosed with depression (28.7%) and anxiety (20.5%) compared to those who were food secure (14.7% and 12%, respectively). In addition, over twice the amount of people who were food insecure had thoughts of suicide in the last 12 months before the study (17%) in comparison to the food secure participants (5.8%).

As food insecurity goes beyond the dinner table, rooting itself in racial disparities, poverty, and the well-being of the people around us, it must be more profoundly looked at to start amending food security and helping the people who are suffering.

III: Off the Same Page

The argument is typically between government and community services when seeking to improve food security. Some experts and organizations say that solutions to food insecurity include using government programs and increased access to food through urban farming. They say U.S. government programs, such as SNAP, can be rejuvenated by Congress, allowing more people to be eligible for SNAP. They also say government support for community efforts, such as urban farming, can help slow the spread of food insecurity. They believe that urban farming will enable people to quickly access healthy food.

Other researchers and organizations say the opposite. They state that SNAP can’t solve food insecurity regardless of eligibility. Families that receive assistance with SNAP still find they don’t have enough money to buy the quality of food they need, leaving them food insecure. They also say that community efforts fail to do what they’re meant to do if not invested in by the community. Concerning urban farming, without active participation from people, it will be more difficult than efficient to help those facing food insecurity, and the upkeep of urban farms may prove itself as nothing but an obstacle.

IV: What Has Been Done

Among the research on improving urban food security, common strategies that were found included price reductions, nutrition education, community engagement, and increased access to local, healthy foods. A 2018 study showed the key way to improve food security is by improving the affected environment. The study was held by B’more Healthy Communities for Kids (BHCK). This trial sought to find if it could increase the consumption of healthier food options for youth (9-15-year-olds) in the low-income area of Baltimore, Maryland. They found that by adding a plethora of low-calorie, low-sugar snacks and drink options in local stores, they were able to increase healthier food purchasing by youth. They also found that providing nutrition education at local recreation centers and after-school programs was a significant influence on the decision to purchase healthier food options.

Another study showed evidence that if the price goes down for fresh produce or a rebate is provided, there is a correlation to an increase in fruit purchased, particularly in low-income neighborhoods. In urban areas such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Detroit, Michigan, the study found that if a consumer didn’t have to pay out of pocket for fruits and vegetables (e.g., using a gift card) or they got cash back, they’d spend more money on produce.

All in all, researchers found that if the focus is on accommodating and adapting to the community needs, slowly, it is possible to improve food security in urban areas.

V: Problems and Solutions

Among the many solutions that are thrown around in an effort to decrease food insecurity, some may work, while others simply won’t. Increasing access to affordable, nutritious food and lowering prices will work; urban farming and government assistance programs won’t. In urban areas, access to grocery stores and supermarkets is not simple. Looking at East Los Angeles, plenty of stores sell groceries around the area.

However, particularly in the parts of El Sereno and City Terrace, it is often seen that residents have limited or zero access to stores within a fifteen-minute walk. This is particularly an issue if residents also don’t have access to a car. It’s already hard enough for residents to find grocery stores within their area, but, if they have no vehicle, it becomes less of a possibility to even get groceries outside of low-income areas.

Though an increase in grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods will increase the amount of food available to residents, that doesn’t guarantee that the quality of food in the stores will be suitable. In addition, it also doesn’t ensure that residents won’t buy unhealthy food options, even if healthy food is available. To solve this problem, we must promote nutrition education.

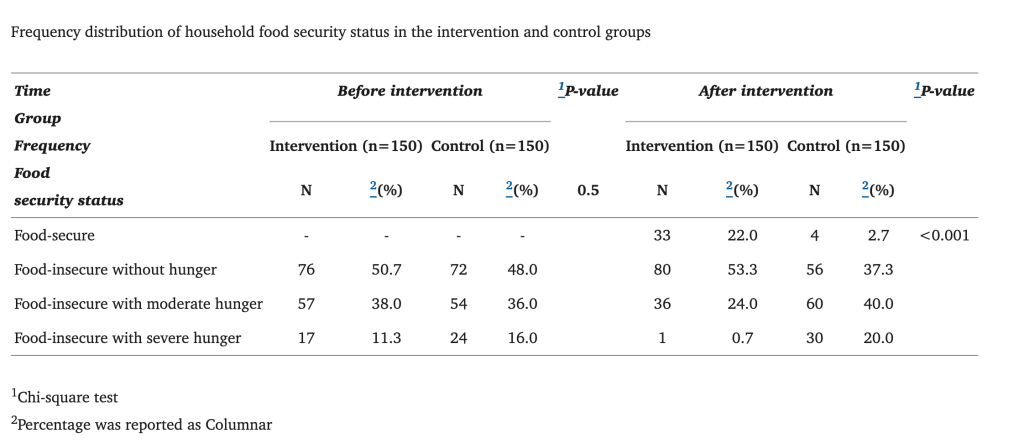

A study held in Zahedan, Southeast Iran, discovered how nutrition education can reduce food insecurity in an urban environment. In the study, researchers found that food insecurity decreased by about 22% after the group had “educational intervention.”

Now, while nutrition education may not be able to solve the economic or socioeconomic factors that cause food insecurity, understanding the healthy food options to buy, how to budget food, and how to prepare food can teach people how to unlearn the consequences of food insecurity as other environmental solutions are put in place.

Another important factor in improving food security is lowering healthy food prices. With these solutions, there are more grocery stores and people who understand healthy food and cooking, but there is a problem: they can’t afford the healthy food in the stores. Research has shown that healthy food options cost significantly more than unhealthy options. To make these healthy food options more affordable, grocery stores and supermarket chains can lower food prices on items such as fruit, vegetables, whole grain bread, low-fat milk, etc., and increase the prices of foods with trans-fats, added sugars, and high sodium.

Now, upon adjusting the environment to help the community most affected by food insecurity, we shouldn’t prioritize urban farming. The USDA defines urban farming as “the cultivation, processing, and distribution of agricultural products (food or non-food) in urban and suburban areas.” Urban farming as a solution to food insecurity doesn’t work as it acts on too small of a scale and can potentially cause more problems than solve the issue we already have. Urban farms face issues as city pollution can impact the quality of crops, people have difficulty accessing farms, and urban farms can displace or disrupt low-income households. That is not to mention that there are not enough urban farms or space for urban farms to make an impact in a city facing food insecurity. Urban farms can not replace pre-existing grocery stores for all residents. It is more advantageous to work on transforming the systems around these food-insecure areas into something more suitable for the community.

Another system that needs to be reconstructed is SNAP. In the U.S., SNAP helps low-income families purchase food to increase access to food and reduce hunger. Yet, SNAP as it is is not going to get people out of food insecurity; it is only going to pacify the problem. Research has shown that SNAP benefits don’t provide stability for families to get the food they need throughout the month, which is referenced as the “feast-or-famine” cycle. It is possible that, without proper nutrition education, some families may consume unhealthy foods during the “feast” portion of the cycle when they first receive the aid. And, when families reach the “famine” stage at the end of the month, they are found to have little left of the funds, leaving them in the same reality they’ve been living. People who must rely on SNAP benefits still don’t have the money to afford food on their own, or else they would be ineligible for SNAP.

So, the issue still exists, but by giving people an inadequate amount of money to help each month, we slow down food insecurity for only a period of time; we don’t make progress in improving food security.

VI: The Root of the Problem

Food insecurity is more complex than hunger; it is also the lack of nutritious foods that fuel our bodies; it is also the worry that one will open their pantry and there won’t be any more food left. The primary issues that cause this do not lie within the people but within the systems around them. It is not fair that on the precedent of one’s salary or skin color, they must struggle to access one of the fundamental things that they need to survive: food. Yet, hundreds of thousands of urban people face this predicament every day.

Their environment only makes matters worse. So, if we want to improve food security, we must accommodate their needs instead of continuing to let them live in areas that are unjust to them. If we continue to let it worsen, it has the power to damage generations.

It is all evident that if we want to create a solution, we must understand the problem. Though, regardless of our understanding, food insecurity is an issue that will continue to be complex and harrowing. But among everything, it is real. It is a real problem that real people in our cities face. And, as leaders, we can’t let them face it alone.

Leave a comment