In the early 20th century, a man of the name Carter G. Woodson would feel as though Black Americans were not being taught enough about where they came from and those who came before them. To seize change, Woodson approached his fraternity, Omega Psi Phi, with an innovation that could spread the stories of his ancestors and their achievements: Negro History and Literature Week. But for Woodson, one week within his school’s borders was not enough. So, two years later, in February of 1926, Woodson and his organization—the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASALH)—set out to the public to declare the first ‘Negro History Week.’ Little by little, parts of America started celebrating Black History; those who came before us in and out of our history books. But, it wasn’t until 50 years later, in 1976, when President Ford accepted ASALH’s expansion of Negro History Week into a Black History Month. Presidents have issued Proclamations for the years since to honor February as Black History Month and all those who make it be.

What we celebrate today is what Carter G. Woodson fought for: for Black Americans’ names to be told and celebrated just as we do for many other influential historical figures. But, it seems that people have lost sight of that purpose. The corporations that run America do not use their influence to advertise those in black history, but only the colors red, green, and black on merchandise. And our education system merely sugarcoats black history, telling the stories of only some and uplifting the white people who had their say in black history.

While black history is technically still being honored in this way, it seems it isn’t doing exactly what it intended. This raises the question: If we’re only partly honoring black history, what exactly are we doing with it?

I: Black History For Profit

Even before Target rolled back on its diversity hiring, I always found it perplexing that Black History Month found a little spot in the front of the store for February, and the moment the first of March came, they’d remove the Rosa Parks shirts off the rack, replaced with spring cardigans. It almost felt like they were using the faces of those who have shaped black history to make a profit. Corporate executive Ezinne Okoro (Kwubiri), who works to initiate inclusivity and change, told NBC she notices more and more companies acknowledging Black History Month, but “the next thing is to challenge them to do more during the year…Let’s not make this about one month of recognition.”

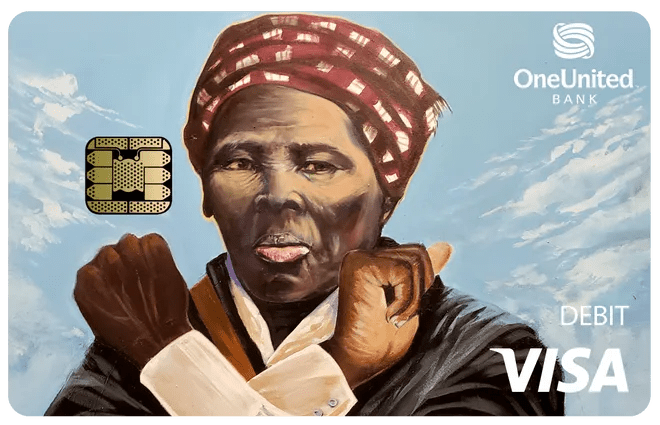

And it’s not only about the lack of recognition of black history, but the misrepresentation. A major part of black history in Woodson’s eyes was about uplifting figures that are not as spoken for. Sure, companies can place Martin Luther King Jr. and Langston Hughes on tote bags and hoodies, but to celebrate the names that nobody knows doesn’t seem like it’s in the cards for them. In February 2020, OneUnited Bank released a debit card with a cover design of Harriet Tubman.

For background, OneUnited Bank, one of the largest black-owned banks in the U.S., has been releasing special edition cards to uplift black culture for years. Yet, the release of the card was met with backlash, with some wondering if this was more disrespectful than it was an homage to Tubman. Professor of History at Morehouse College, Frederick Knight, said it may have been more respectful to represent a lesser-known figure, like Maggie Lena Walker, who had an essential role in elevating economics for black people in America. Knight said, “There are more appropriate people they could have used this opportunity for, rather than take advantage of an iconic person like Harriet Tubman.”

While there is no right way to celebrate Black History Month, there are wrong ways to celebrate. When companies only come around once a year to celebrate black people, and some of them spend the rest of the year working against black people, their celebration of black history isn’t genuine; it’s exploitation.

II: Injustice In Education

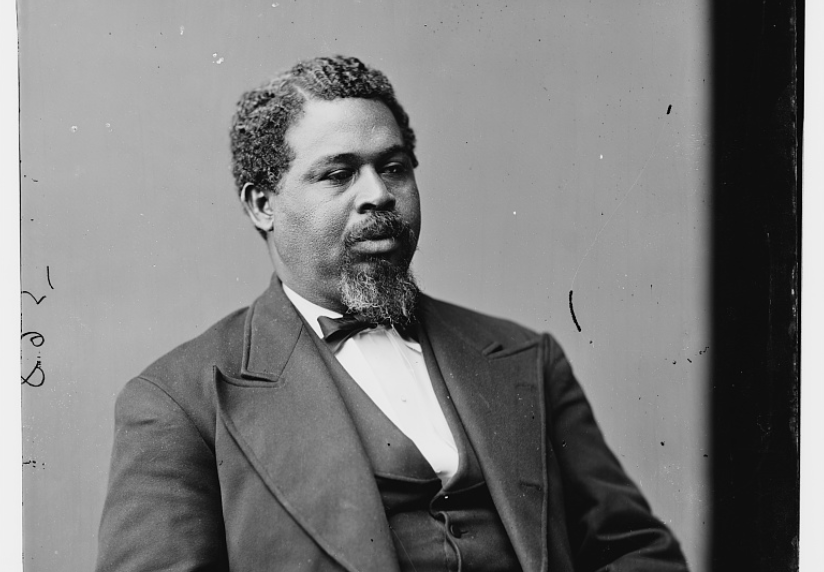

I never learned about Angela Davis, or Robert Smalls, or Medgar Evers. Their names were never in the history books and their actions are more challenging to research than the likes of Martin Luther King Jr. or white figureheads. It’s perturbing to think that if I had relied solely on the education system, I still wouldn’t know their names.

Yet, teachers are hesitant to teach more black history. Why? They don’t want to teach “bad history.”

Black history is complicated. It isn’t merely those who have been the first to break records like Simone Manuel or inventors like Garret Morgan; it is also pain and suffering. It is white people destroying the lives of black people for hundreds of years. It is even black people being contentious with each other on civil rights. When we don’t teach people about all that has happened to black people throughout history, then we are not teaching history; we are telling false tales. LaGarrett J. King, a professor at the University at Buffalo, wrote, “History is all about learning about the humanity of groups of people, the good, the bad, and the ugly. Our heroes are flawed because they are human and not perfect. When we resist teaching those concepts in Black history lessons, we devalue Black people’s full humanity. If we only allow a respectable history that represents us in a pleasant light, what message do we send our students?”

Beyond African-American history, black history in places such as the U.K. has also been minimized to sugar-coated stories that uplift white history. The research paper, Applying a Racial Microaggressions Framework to Black Students’ Experiences of Black History Month and Black History by Nadena Doharty explores how the curriculum in the U.K. plays a role in diminishing black history, stating, “The consequence of reducing Black History to a non-statutory place on the KS3 [Key Stage 3] History curriculum is that schools may only engage with elements of it where teachers find areas of converging interests, such as Britain’s role in abolishing slavery. As a result, Whiteness, the foundation of institutions, has the power to dominate Black History’s scope and direction or not engage at all. The Whiteness-as-normal construction of Britain’s past could explain the disturbing poll conducted by YouGov showing that 44% of British people were proud of Britain’s history of colonialism (The Independent 2016).”

Teaching only one part of history, and in particular, the parts that have to do with whites, is narrowing the scope of black history. This affects the efficiency of getting the true history out to people and impacts those reading the history books. If the education system only teaches students that black people are merely victims and that white people have superiority in history, then black students are not going to have the notion that black people throughout history are more than victims of constraint. Further, it is reinstated that the black leaders who make it in the history books can’t cause too much of a rift, and white people have to agree or coincide with their actions.

Doharty says, “Exploring nuances within racial microaggressions, allowed for the identification of instances during History lessons that negated, nullified, excluded and marginalized Black students…these instances are legitimated by systemic racism within the very construction of the Key Stage 3 History curriculum that reflects the same demeaning message to Black students: their histories are only significant where they provide a function.”

III: It’s More Than What We Do

Black History Month is a month to celebrate all of black history. It is a month that we celebrate those who have made it possible for us to be free and how they made that possible. We can’t spend this month avoiding the ugly, painful side of history, just as much as we can’t go half on celebrating the goodness done by black pioneers every day.

Still, a change needs to be made within this month. The issue of Black History Month in lies in the way we represent it. We need to relocate the focus of Black History Month once instilled by Carter G. Woodson, and we need to stick to it in February.

Beyond that, we can’t settle for companies and schools that only care about this month once a year. We have to continue to see the achievements of black people from all around the world, just as we were taught to do so for white people.

So, as Black History Month reaches its end, I want to remind you that black history isn’t just February; it’s 12 months of worldwide history.

Leave a comment